Big (and Fast) Quantum Data

"Of all the theories proposed in this century," physicist Michio Kaku wrote in Hyperspace, "the silliest is quantum theory. In fact, some say that the only thing that quantum theory has going for it is that it is unquestionably correct."

Last month, our client Accurate Append, an email and phone contact data quality vendor, blogged about a big space data conference, and described promising developments in the use of data analytics to measure greenhouse gases based on satellite imagery, to identify organic molecules and methane on other planets and moons (critical to the search for the origins of life) and more.

But how about a deeper dive into something even more complex? The particles (like photons and electrons) that make up the substance of the universe behave in really strange ways if we look at them closely. They have a "reality" very different from classical descriptions of matter as stable and consistent. Understanding that strange behavior—and then even harnessing it, or flowing along with it—is the challenge of applying quantum theory, and this has world-shattering implications for big data and artificial intelligence, to say the least.

It really depends on who you ask, of course, whether this is a good thing. Shouldn't we be able to break codes used by criminals or terrorists? We may be heading into a brave new world where security and insecurity co-exist along with the on, off, and on-off of quantum states. An expert in "Ethical Hacking" said back in 2014 that told Vice in 2014 that "the speed of quantum computers will allow them to quickly get through current encryption techniques such as public-key cryptography (PK) and even break the Data Encryption Standard (DES) put forward by the US Government."

In the most oversimplified of nutshells, quantum computing goes beyond the binary on/off states computer bits normally operate under, adding the additional state of on and off. The main consequence of this third state is that quantum computers can work "thousands of times faster" than non-quantum computers—beyond anything that could be otherwise imagined. That speed also adds to the security of quantum data. Experts call it un-hackable, which is pretty audacious. Some of the basic everyday miracles of quantum physics also make their way into quantum computing, like "entangled" particles being changeable together even if they are far apart. This provides a way of essentially "teleporting" data—transferring it without fear of being intercepted. Chinese scientists seem to have taken the lead on the un-hackable quantum data plan. Since there is no signal, there is nothing to intercept or steal. To put it in even simpler terms, the data being shared is, in a sense, the same data. It's like existing at two distinct points in the universe simultaneously but only as one unit. More precisely, you've created a pair "of photons that mirror one another." This indeterminacy leads to the possibility that many of the "laws of science" we take for granted are just arrangements of things in relation to other things. Gravity itself, and many of the behaviors of space and time might actually be "correcting codes" at the quantum level.

Qbits, which are these nonbinary computer bits we're talking about, can be made by superconductors that maintain a quantum state. This requires extremely cold temperatures—close to absolute zero; colder than the vacuum of space. Underlying these miraculous evolutionary steps is the quantum theory's embrace of "imprecision" in a computing world that has mostly relied on precision and predictability. This makes quantum theory natural kin to artificial intelligence since AI aspires to teach computers how to "handle" and process imprecision.

In some ways, embracing imprecision in computing technology is similar to the implications of philosophers rejecting binarism in the 19th and 20th centuries. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, for example, in the early 19th century, developed the dialectic to do justice, as many of his interpreters have put it, to the reality of the half-truth, to the idea that things may be in a state of development where they are neither and both one thing and/or another. In a very different way, the Danish theologian Soren Kierkegaard sought the rejection of absolutes and the embrace of absurdity, a kind of simultaneous being-and-non-being. Werner Heisenberg, one of the founders of quantum theory, seemed more like a philosopher than a scientist when he wrote "[T]he atoms or elementary particles themselves are not real; they form a world of potentialities or possibilities rather than one of things or facts."

The implications for big data are immeasurable because quantum computing is to nonquantum computing what the speed of light is to the speed of sound. "Quantum computers," says Science Alert, "perform calculations based on the probability of an object's state before it is measured - instead of just 1s or 0s - which means they have the potential to process exponentially more data compared to classical computers." All of this culminates in Lesa Moné's post on quantum computing and big data analytics. With quantum computers, Moné writes, the complex calculations called for by such analytics will be performed in seconds—and we are talking calculations that currently take years to solve (and are sometimes measured in the thousands of years). Quantum calculations will change the very nature of how we view the interaction of time and information processing. It's something on par with the discovery of radio waves, but given that we'll be crunching years into seconds, the social impact may be much, much larger.

Data, Election Hacking, and Paper Ballots

Thomas Paine wrote that "the right of voting for representatives is the primary right by which other rights are protected." Taking away that right reduces us "to slavery" and makes us "subject to the will of another." Regardless of whether you're on the left or right, Americans value that kind of autonomy—that we choose the rule makers and enforcers, that we periodically get to choose new ones and whether to retain incumbents. How to protect the integrity of that process, so that its outcomes actually reflect our conscious preferences, seems to be as important a question as any that law and policy makers could ever ask in a democracy.

Data and its processing are commodities and conduits of power, and because of this, there will always be attempts to steal and manipulate them. Our SEO client Accurate Append, a phone, address, and email contact data vendor, recently wrote about the danger of fake data, and hacked elections are a manifestation of the same overall aim: to distort the will of voters and undermine people's participation in civil society.

For people who work on improving the electoral process, and those of us offering services for candidates and leaders to better reach voters, this is also a question of professional importance. It's personally frustrating for those who offer data, analytics, other informational services that help campaigns learn more about their constituents. Hacking undermines the effort to construct electoral strategies commensurate with the needs and perspectives of the real people who are voting.

News media is buzzing that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is blocking legislation to address election hacking at the federal level. And states are not moving either. The Verge reports that although progress has been made on moving back to paper ballots (only 8 states remain paperless now compared to 14 in 2016), "most states won’t require an audit of those paper records, in which officials review randomly selected ballots—another step experts recommend. Today, only 22 states and the District of Columbia have voter-verifiable paper records and require an audit of those ballots before an election is certified." As we'll shortly explain, that extra verification step is necessary because even paper ballots are vulnerable to manipulation.

Much of what we know about the ability to hack into things like elections is due to the efforts of organizational hacking conferences like DefCon, which gathers experienced hackers at conferences to discuss the ways that security may be open to breach.

The work they do, which was featured at a recent annual conference, is fascinating. In addition to election hacking, which we're discussing here, hackers and scholars of hacking research things like whether AI and robots are subject to sabotage via electromagnetic pulse (EMP). It all feels very James Bond. But the most immediately relevant stuff is voting machines, systems, and databases—all set up as the "Voting Village" at the conference, with the aim of promoting "a more secure democracy." These "good guy" hackers find ways to remotely control local voting machines, "the innards of democracy," so that the public can be aware of potential threats and constantly demand solutions. As one hacker put it, "these systems crash at your Walmart scanning your groceries. And we're using those systems here to protect our democracy, which is a little bit unsettling. I wouldn't use this . . . to control my toaster!"

This work is important even if all states switched back permanently to paper ballots, because some kind of technological facilitation, intervention, and processing is inevitable, and as long as such activity contains data shared between machines, it's subject to outside sabotage or manipulation. Freedom to Tinker has an outstanding list of the ways this could happen in a paper system. Hackers could hack the software used in the auditing and recount processes, and avoiding the use of computers during that process is impractical in contemporary society. "For example, we may have print a spreadsheet listing the “manifest” of ballot-batches, how many ballots are in each batch; we may use a spreadsheet to record and sum the tallies of our audit or recount. How much of a nontrivial “business method” such as an audit, can we really run entirely without computers?"

Of course, as the article adds, one could simply manually manipulate the recount process with a "bit of pencil lead under your fingernail," but at least at that point there would be people to catch locally doing such things. The call for "careful and transparent chain-of-custody procedures, and some basic degree of honesty and civic trust" is easier to enforce in person than across bytes, air, and cables. In the meantime, though, paper ballots aren't perfect, but they are the cornerstone of addressing current threats to election integrity.

Healthcare Staffing Is the New Data Commodity

If you have nursing credentials, and are willing to travel to meet the ever-shifting (and ever-growing) demands of healthcare providers, chances are that your contact information will be part of varying bundles of data bought, sold, or traded by nurse recruiting websites. This isn't necessarily a bad thing—and it's a subject I think about a lot since my SEO client Accurate Append is in the business of providing the most accurate email, cell phone, and landline contact data.

Healthcare professionals are the gold standard of the contemporary tight professional labor market. Healthcare CEOs list their biggest rising expense as the money they spend competing for talent. Hiring rates are incredibly high now and are expected to either stay the same or even grow in 2019. According to the "Modern Healthcare CEO Power Panel survey," about 75 percent of CEOs responded that "front-line caregivers are most in need." No wonder the unemployment rate for practitioners is only 1.4%, while the rate for assistants and aides, higher at 3.4%, is still well below the typical 4% unemployment rate. If you want to be in demand, be a healthcare professional.

And if you want to be in even higher demand, be a Registered Nurse (RN) who can travel. These stats are unbelievable. RN employment overall will grow 15 percent over the next 8 years—higher than pretty much any other profession. Travel nurses are hired on contract to fill temporary gaps in nursing, and the industry is benefiting from increasing participation by states in the Enhanced Nurse Licensure Compact (eNLC).

The recruiting game for these (often highly-specialized) travel nurses is in full steam. Kyle Schmidt of the Travel Nursing Blog has a fascinating piece on the emerging market for the personal contact information of nurses who make themselves available for travel services. This demand is met by gathering data from prominent services like travelnursing.org, travelnursesource.com, rnvip.com and others, but it's also met by more traditional healthcare staffing companies which, although they don't sell contact information to their partners, simply generate their own leads to fulfill their clients' needs.

When this data is collected via the web, it's done through website visits where visitors are encouraged to provide their contact information. Those sites are using old-fashioned, but reliable, methods of getting people there: Kyle points cites stats by Conductor, a digital marketer, that "47% of all website traffic is driven by natural search while 6% is driven by paid search and only 2% is driven by social media sites." Paid advertisements are virtually ignored in comparison to naturally clicked links, while "75% of search users never scroll past the first page of search results."

How are nurses convinced to provide their contact info? The answer is through the advertisement of "broadcast services," which promise to provide candidates' information and availability to agencies. The business model works even if the broadcast service doesn't get a lot of money for providing the data, because the web sites are very basic, often managed through content-management systems, and don't need to be heavily maintained.

This steady (and often high-speed) increase in recruiting needs is part of maybe the longest term employment trend in the U.S. today. Hospitals have been using contract labor to fill in for massive nursing labor shortages at least since the late 1990s. Over a million and a half jobs were added from 2004-2014, and as we know, these vacancies kept growing in the last five years. A June 2019 market research report sheds some interesting light on the healthcare recruiting industry--some facts that might explain why the recruiting game for nurses seems so data-driven (and dependent on contact info-fishing at such a volume-driven level). While we know the labor market is competitive, what we do not know is whether particular states and regions will have consistent demand for nurses. This is because, while we know government spending on Medicare and Medicaid is expected to increase in 2019, the ongoing political volatility around healthcare spending means that there may be bumps in the road, unexpected windfalls in unexpected places, and unexpected losses of funding as well.

All of this leads me to ask whether contact info data collection and distribution for the nursing industry might be streamlined and made more efficient over time. We know that hospitals' human resources departments "use analytics for recruiting, hiring and managing employees," but there's a divide between how big and small facilities collect and manage this data. According to the Nurse.com blog, big hospitals "have sophisticated human resource management systems for employee records and talent management, while small facilities and clinics often rely on free analytics tools such as job sites, email clients and search engines"—analytics tools provided by sites similar to the data collection and distribution sites mentioned earlier.

Leadership as Dialogical Communication

South African artist and sculptor Lawrence Lemaoana has a piece called "Democracy is Dialogue" standing in front of old Johannesburg City Hall. The statue is of "a woman protester with a baby strapped to her back. She has a protest placard in one hand and a candle in the other to light her way." Lemaoana has been a fierce post-apartheid social voice and was a critic of president Jacob Zuma. President Zuma would often publicly raise his fist, a sign of victory, but for Zuma, a call to silence criticism.

Public communication is not always communication geared toward dialogue. Donald Trump rose to the presidency through, among other things, his aggressive use of Twitter to draw attention to himself and to criticize others. Twitter's simplicity and tendency to vitriol set the tone for Trump's messaging. The communication wasn't multi-directional; it wasn't a tool of dialogue. Nevertheless, "In a 3–0 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that President Trump's practice of blocking critics from his Twitter account violates the First Amendment." What Trump thought was a bullhorn at least required him to allow others to scream back at him. Still though, not a dialogue.

But the Second Circuit Court's rationale for the decision draws from a more civic-minded philosophical well: because Trump's Twitter account was a government account—official seal, held up as such, "with interactive features accessible to the public"—the First Amendment was relevant and in need of protection. After all, as the court points out, "not every social media account operated by a public official is a government account," so if Trump had wanted to rant without response, he could have done so on an account not specifically identified as governmental. He even arguably could have done so on his reelection campaign accounts. "The court found that President Trump, therefore, 'is not entitled to censor selected users because they express views with which he disagrees.'"

The underlying philosophical principle is just as important as the legal distinction. That underlying principle is that public, government-mediated communication with public officials is dialogical. Dialogical means having the "character of dialogue," a discussion between two or more individuals.

That's a profound distinction, even if it comes off as functional and factor-based in the court's analysis. Democracy is a process, but it's also an approach. For proponents of more participatory democracy, that approach is, among other things, dialogical—based on ongoing conversations between officials and their constituents.

But even though a court can rule that people have a right to tweet back to a public official, that doesn't mean doing so constitutes meaningful public or constituent dialogue. Even if there are dialogic elements to social media, its underlying structures and its practices in a mass marketing context may undermine whatever dialogical function it has. Samantha McDonald, who studies how technology mediates communication between citizens and policymakers, writes at her blog: "major social media players like Facebook and Twitter were never designed to be spaces for quality policymaker engagement. Just ask Congressman Rick Crawford, who replaced Facebook with his new texting application. Or Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who points out that these platforms are huge public health risk. In addition, why is Congress communicating to constituents through platforms that sell citizen’s data?"

It's important to remember that not all constituent communication is about important policy dialogue (in another piece, McDonald points out that congressional staffers "report that contact can be untimely" or consist of "emotional reactions to government issues that the office cannot help"). But policy discussions with constituents are possible. Focused dialogue which is proactive and "hard-wired" into a deliberative event can result in "diverse participation," particularly if accompanied by "balanced, factual reading material for participants; single topic focus; a neutral, third-party host; and live member participation." Structured communication is also possible through constituent-focused CRMs—designed not for consumers, but specifically to foster official-constituent dialogues over time.

One Quick Trick for Increasing Your Podcast Plays

Back in 2009, I produced and hosted a no-budget podcast about the emerging use of social media in government called “Gov 2.0 Radio.” If I were to do it again today, there’s one tool I’d definitely use to grow my audience: ActionSprout.

During my Gov 2.0 Radio days, Twitter was often how I’d juice exposure for my new episodes and related blog posts. I’d also use Twitter and RSS feeds to gather news about emerging Gov 2.0 trends and often published link roundups. If I’d had a tool that brought the best performing content from Governing, Social Media Today, and the rest of the crumbling Web 2.0 media right to me, with publisher and advertising tools to boot, maybe I’d still be interviewing up-and-coming PIOs to this day.

I’ve worked with ActionSprout for several years, first as an early NationBuilder partner, then to help the company distribute $2 million in Facebook ad credits to nonprofits. Today, I am organizing a network of news and good government organizations to curate and promote quality anti-corruption news on Facebook using ActionSprout’s tools.

If I were podcasting or producing video shows today, I’d simply load a list of Facebook pages for my best sources into ActionSprout Inspirations, sort for the top performing posts each day or week, schedule out my favorites with new commentary, and share the roundup in my broadcasts.

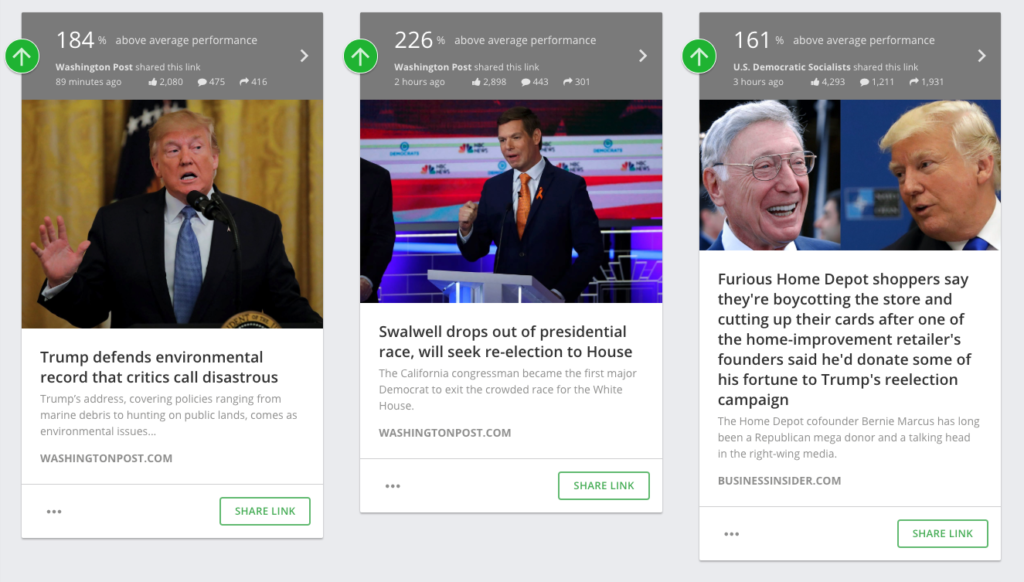

Here’s an example from a list of political sources I’m presently following:

How does following and sharing relevant viral stories help a podcast grow its audience? One, drop a link to your relevant shows into your commentary on a trending story that is going to outperform and reach beyond your fan base. Two, use the ActionSprout Timeline feature to identify your top trending posts on your own page, edit post commentary with a relevant link to your own content, then use ActionSprout’s advertising tools to boost the viral content. Don’t miss the opportunity to repost your best content, either - Facebook will find new, relevant audience for it, not repeat it in your fans’ feeds.

What if you want to collect more information, such as text opt-ins, from listeners? You can use a phone append database from a vendor like Accurate Append with a data append API to validate forms in real time. You can also use ActionSprout’s petition tools to begin building an email list based on your Facebook fans.

Engaging deeply with a listener base, whether through public and exclusive groups (a good example here is Beep Beep Lettuce, which has a public Facebook page, a group for supporters, and a Discord channel for the most hard-core fans), Patreon updates, an email newsletter, or even text subscriptions, is foundational to long-term audience growth.

Join ActionSprout's government accountability network—free for media and nonprofit organizations.

Local Government Transparency as Value Criterion

Stick the word "transparency" into a news database. Limit the search to the past week. You'll pull hundreds of links: letters to the editor on a local government body's lack of transparency. Congressional hearings on transparency in the federal judiciary. Pushes for transparency in health care charges. The applicability of police transparency laws to various police records. Transparency in all levels of decisionmaking that affect the public.

We hear the word "transparency" all the time. It's a "god" term in nearly every aspirational statement of nearly every political ideology. We don't spend a lot of time contemplating those times when transparency might not be the highest value (protecting the privacy of vulnerable people, allowing public officials a little deliberative space rather than reminding them they're always essentially on television, and so on) because we've seen too many instances where secrecy has been abused. Transparency not only has the denotative meaning of openness, but the connotative meaning of: essential for democracy.

Although American legal scholars have long characterized states as laboratories for democracy, a growing consensus is building around municipalities as better serving that space. Municipalities have a disadvantage, resource scarcity, that actually interacts with the advantage of direct contact with constituents—everyone gets to complain and argue about that scarcity together.

What is transparency? According to one extremely in-depth treatment of the topic, "[t]ransparency is understood as the opening up of information on actions and laws to the public, providing citizens with the tools to improve understanding, vigilance, and communication. Coupled with action from the public and media, this should lead to accountability where public officials take responsibility for their actions (or inaction)."

We hear a lot about how technology aids secrecy—and it certainly does. But technology also supercharges the potential of governments ethically committed to transparency. As Catherine Yochum points out, technology has made direct participation easier than it's ever been in history. It allows citizens to participate from their homes, it facilitates the establishment of what Yochum refers to as "community dashboards." Cities looking to implement these sort of systems should seek out CRM and data analysis software built specifically for government.

Although accessing these platforms requires investments from the jurisdictions that use them, the technologies involved aren't just commodities. So when Yochum writes that municipalities "are, for lack of a better word, 'competing' against other cities for residents, businesses, tax dollars, state grants, and federal grants,' I don't know if the competition metaphor is wholly appropriate. People don't choose where to live like consumers choose products from vendors—at least the vast majority of people don't. And relationships between cities are part of creating political geographies that work for people in a complex, economically insecure, and interdependent material landscape. In fact, cities and counties can work together for even greater transparency and efficient information delivery than they could alone, perhaps using joint powers authority like the kind that exists in California. Speaking of California, the state has other transparency-facilitating advantages as well: a robust home rule law, as well as being the pioneer of the Public Records Act, enacted in the late 1960s, requiring "municipalities to disclose government records to the public."

Finally, U.S. municipalists can look internationally to see how voters and residents can empower themselves using transparency tech. Kenyans are enacting tech fixes to make proceedings of parliament more accessible. Jordan—a monarchy—is involving citizens in direct decisionmaking via a system called Ishki. Chile has the very nicely named Vota Inteligente, "informing Chilean citizens about corruption and policy debates through the use of social media." Seoul has its own corruption reporting systems, while Peru, Russia and Germany have all adopted constituent conversation systems. And "[i]n India, technology and independent mass media has also allowed people to put pressure on the government to act against corruption and be more transparent . . . in Mumbai a number of groups of 'activists, geeks, data people, lawyers and techies' hold 'datameetings' to discuss how data and technology can be used transparently."

Transparency is seen as a core value—that is, a value that informs other values and policy criteria. It's really a synthesis of the right to know with freedom of expression, as either of those values by themselves would be meaningless without the other. Both of these are enhanced by technology in accountable hands.

Google and the Right to Be Forgotten

The "Right to Be Forgotten" doctrine is controversial in the United States in ways that frankly surprise most Europeans. The latter are used to the eternal complex struggle to balance the rights of individual and community, and are not used to the deference given in the U.S. to large corporations. So when a "leading French consumer group filed a class-action lawsuit" last week "accusing Google of violating the European Union's landmark 2018 privacy rules," this hardly raised an eyebrow in the European press, but plenty has been said about it in Google's home country.

The lawsuit was filed in an administrative court in Paris by UFC Que Choisir, a consumer advocacy group. It seeks a little over a thousand dollars in damages for each of 200 users. The EU rules in question are known as GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), and they prohibit operators from publishing private data on non-newsworthy individuals. Google has responded in the media by saying its privacy controls are consumer-driven and adequate.

Some legal scholars argue that the U.S. should follow suit, implementing a right to be forgotten doctrine, which would protect both adults and children from humiliation and bullying online. Not just because parts of the unregulated online community can, as the Connecticut Law Journal pointed out years ago, be literally violent and traumatic. Which it can. Understanding why some people believe we actually can balance privacy and freedom of speech requires at least an acknowledgment that there are good arguments for excluding "a right so broad that wrongdoers and corporations can expunge important data relevant to, for example, consumer and investor decision making."

This is in part a technological question. "The Internet does not have to preserve information forever," and so proponents of a right to be forgotten are essentially saying that technological possibility needn't determine ethical permissibility. RTBF proponents say that an egalitarian society requires the right to a private life separate from capitalism's colonization of public life, if that's possible. There is also a wide distinction between the kind of data append, email, and consumer marketing data long used to reach consumers privately and the detailed public dossiers of individuals created by and accessible through today's internet giants.

Julia Powles, researcher in law and technology at the University of Cambridge, argues that the private "sphere of memory and truth" must be kept separate from public memory in order to preserve that part of freedom that keeps egalitarian values from becoming inegalitarian hierarchies. Homeland Security NewsWire's Eugene Chow argues that the European rules have made life better for internet users, where Europe's "conception of privacy" could set a model giving "Americans [ . . . ] a legal weapon to wrestle control of our digital identities." There are limits on even robust RTBF policies, and people can't hide information just to make their lives more convenient or escape accountability.

On the other hand, there are good reasons to be skeptical of RTBF. It lacks clear standards, checks and balances, and as Jodie Ginsberg of Index on Censorship points out, the appeals process isn't what Americans would expect. Speaking of one particular EU court decision, Ginsberg calls it a "flabby ruling" and argues that, even aside from the free speech questions, there are practical resource issues: "The flood of requests that would be driven to these already stretched national organisations" for RTBF status should deter people from turning the right into "a blanket invitation to censorship." And to be sure, these requests will include public figures seeking to game the rule, such as the case of an actor requesting the removal of news articles about an affair they had with a teenager, or the politician who wanted stories of their erratic behavior wiped.

But in the final analysis, the experiences of totalitarianism in the 20th century suggest that if we can't trust governments with our private lives, we can't trust corporations either. Both the far right and Stalinism produced, as one scholar puts it, "shockingly tight surveillance states."

As Jeffrey Toobin points out, it was the EU's proximity to such totalitarianism that has led to the "promulgat[ion of] a detailed series of laws designed to protect privacy." We really can't trust hierarchical authority, whether it comes from the market or the ballot box, even if we have to work with such forces. So even if it's not an EU-style RTBF, the experience of Google in Europe suggests that Americans should at least come up with some reasonable guidelines to protect the privacy of non-newsworthy data—whatever we might decide, through endless deliberation, that might mean.

Comprehensive Communication Tools and the Culture of Government Teams

How is organizational culture changing in government offices? And how are collaborative platforms part of that evolution? Although this is far from a scientific observation, I think as our political culture has embraced more grassroots populism over the last several years, space for similar participatory culture has opened up at least among the structures and blueprints of government org culture. We've come a long way since I first started the "Government 2.0" podcast in 2009!

We can see part of this transition just by reading what people have written about such organizational culture over the last several years. A 2013 article mentioning "participatory leadership" had good suggestions for its time, but seems quaint in that it mentions nothing about technology, nothing about communication and collaborative work platforms.

So even though the article calls for "mechanisms such as an employee advisory team that allows employees to provide input into policies and programs to design a first rate work environment," we can picture all of these programs being enacted in real time, absent shared work platforms beyond Google Docs, perhaps in a meeting room like the one in The Office. The article even mentions "open and honest communication . . . with a handwritten note," and while I hate to be dismissive about the power of handwritten notes, let's just say that nowadays it's the very exceptionalism of a handwritten message on paper that makes it noteworthy. After all, we can private message people--or praise them publicly--on integrated platforms like Slack.

Fast forward to 2017. Slack and Asana are in play. But not all government workplace cultures are participatory. This piece in Governing took me by surprise because it led with the negatives of public sector workplace culture and almost reads like a libertarian manifesto: "Curating a healthy workplace culture in the public sector poses unique challenges," it reads. "In contrast to the business world, governmental organizations have constantly evolving priorities, excessive bureaucracy, shifting political winds as elected leaders come and go, ebbing and flowing budgetary resources, and, too often, a lack of understanding by leaders and managers of culture's power and influence."

To solve these things, the article points to the example of Coppell, Texas's city government, which has cultivated a "high-performance workplace culture" including "a code of ethics, an oath of service, behavioral guidelines and what the city describes as a 'culture of credibility'" which is "reinforced through extensive learning/training programs and a variety of other means." All of which sounds incredibly disciplined, probably efficient, but not necessarily participatory. I fear that such a regimented work culture is susceptible to groupthink and bad decision-making unless it feels democratic and deliberative to team members. I have no idea whether the good people in the Coppell city government have such a voice, but the article doesn't flag it.

But then check out this 2018 piece, "Organizational Culture in Local Government," and it's also in Texas--in fact it's the Texas City Management Association's blog. This almost reads like a worker cooperative: "mutual trust, fairness and justice for all employees, recognition of individual worth . . . People join for the purpose of giving rather than to get." The emphasis is clearly on building non-punitive, non-fear-based, participatory culture. The article goes on to emphasize that leadership shapes the organization's culture. But again, nothing about communication platforms.

The only posts that seem to account for the role of comm tech in creating an egalitarian workplace culture are those written by the people selling the apps, like Staffbase; their blog contains "11 Ideas How to Rethink Internal Communications—and Boost Your Employee Engagement," and the suggestions aren't bad--and they recognize the role of the platform. The post points out that the rising generation is looking for values alignment, and in my experience those who look for values alignment in their organizations almost always look just as hard for participatory work environments.

Integrated communication platforms can, in fact, establish trust by providing a natural, organic, accessible method of collaborative work and easy, horizontal communication. This is all because the wave of democratization and grassroots politics that we're seeing grow in the political realm is also taking shape in government workplace culture, making platforms that integrate internal and external government communications, including texting and service requests, normal instead of the exception. The development of collaborative platforms isn't just a business evolution. It's a governance evolution and, really, a humanity evolution.

Juicing Your Twitter Visibility To Get Quoted by the Media—Secrets of an Unabashed Reply Guy

I want to tell you what I did to get millions of new Twitter impressions and win coverage in five news articles in just 28 days.

I was quoted fighting for progressive values here:

Trump Loses It On Twitter And Attacks Fox News After Bernie Had Successful Townhall

Bernie Sanders answers Lindsey Graham’s jab on letting terrorists vote by pulling the race card

‘Not a radical idea’? Bernie Sanders doubles down on giving violent prisoners the right to vote

President Trump Schooled Bernie Sanders On Our Booming Economy

***

For a long time, whenever I'd give a talk or introduce myself on a panel, I'd mention running for Congress in 2009 and getting more Twitter followers than votes. It's a good laugh line, and blunts the pains of that loss. Today, more new people follow my Twitter account in a month than the 347 who voted for me in that special election.

Still, those were heady times. National Journal wrote about fundraising through Twitter (you didn't) and the party was calling from DC to learn how I'd come out of nowhere to score breathless political coverage from coast to coast. "Here’s another milestone for Twitter," Politico reported. "The first congressional candidate has announced his campaign through the trendy social networking site."

Thanks to the bombast of our current President, Twitter is hot, again. "See what’s happening in the world right now," it promises. And any candidate or media figure who wants to be taken seriously, who wants to win in our frantic media environment, has to have Twitter game.

I've recently been experimenting with taking Twitter more seriously again as a branding tool - working with a coach and writing about my assumptions and experiences, first for data appending vendor Accurate Append (client), "How Influencers Use Twitter Replies to Build An Audience," then in more depth for Campaigns & Elections' Campaign Insider, "Five Ways to Explode Your Twitter Game." Like most of my strategic and tactical work, I am sharing this to help those who aren't able to work with big agencies level up with those who are—these are the simple lessons that helped me take a decade of tweeting from middling success to millions of impressions and tens of thousands of dollars in earned media exposure with just weeks of practice.

Our work proved that you can ramp Twitter results dramatically in just weeks: more impressions, more followers, thought-leadership recognition like the C&E article above, visibility in industry viral media stories, and tens of thousands of visits to your Twitter profile.

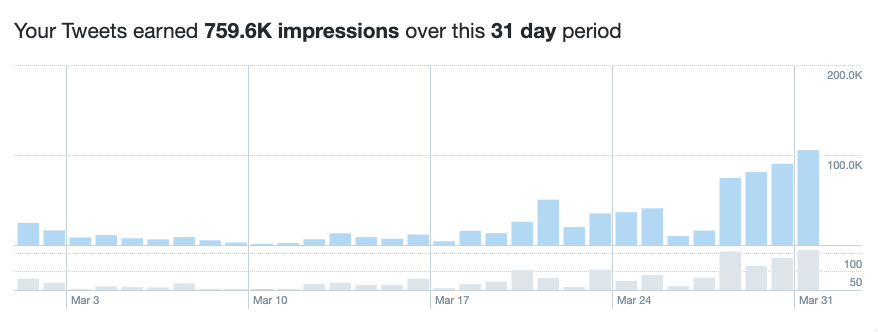

Here's a graph of my Twitter stats from March - at the tail end, I'd started to practice lessons from my coach, Nathan Mackenzie Brown, founder of the viral Really American Facebook page:

One thing that immediately jumps out is that I had to tweet more often in order to get more content views. Twitter visibility does usually grow with activity. However, a big lesson I took from Nathan is that if I wanted to be more successful using Twitter as a business tool, I needed to be much more thoughtful about my use. No more scrolling Twitter restlessly at night. No more tripping on uneven sidewalks while lost in Twitter addiction. Instead of letting the Twitter algorithm work me on my phone, I deleted the app and began constraining my Twitter use to my most productive times of day - and desktop use only. I would work the algorithm instead of letting it work me.

The results were dramatic. This is my stats graph for April:

The critical success factor for blowing up your Twitter visibility is targeted replies. They get your tweets in front of hundreds of thousands of people, and they get your tweets into news coverage, like Mediaite, Heavy, and the George Takei pub Guacamoley!

Saucy replies to a single Trump tweet account for the big mid-month spike above. Twitter also prominently features viral reply threads, giving you lots of digital real estate to get a point across. The winning "reply guy" strategy isn't trying to get attention from the original target, it is about drafting on the target's viral attention and audience. If you're looking to grow on Twitter, I hope you'll look at the articles linked above—and don't forget that once you catch a top reply, keep replying. All of my recent big weeks on Twitter have come from a series of replies that Twitter helpfully turned into a feature.

One caveat for follower growth is that tangling with ideological foes usually won't win you new fans. It is also important to update both your notifications for users and for your own replies—you want to be first in with a strong, stand-alone comment in viral Twitter users' replies, and to tamp down the trolly responses you'll get when your own tweets go big.

I recently wrote about how newly registered voters in California are, in overwhelming numbers, deferring party registration. Astute political friends pointed out that California’s new “motor voter” registration at the DMV defaults to “No Party Preference”if a party isn’t selected and it’s no big surprise that while the Democrats are doing much better than Republicans, most people aren’t too jazzed about picking a political party.

In October, 4,725,054 Californians were Republicans, 5,419,607 NPP, and 8,557,427 were Democrats. The total lead in Democratic registrations, often cited against Republicans, hides a much more significant trend in voter attitude. In the five months between reports, the Democrats added 119,159 new voters, growth of 1.4%. NPP registrations, however, grew 8.35 times as fast and for every new Democrat, five Californians went independent — more than half a million.

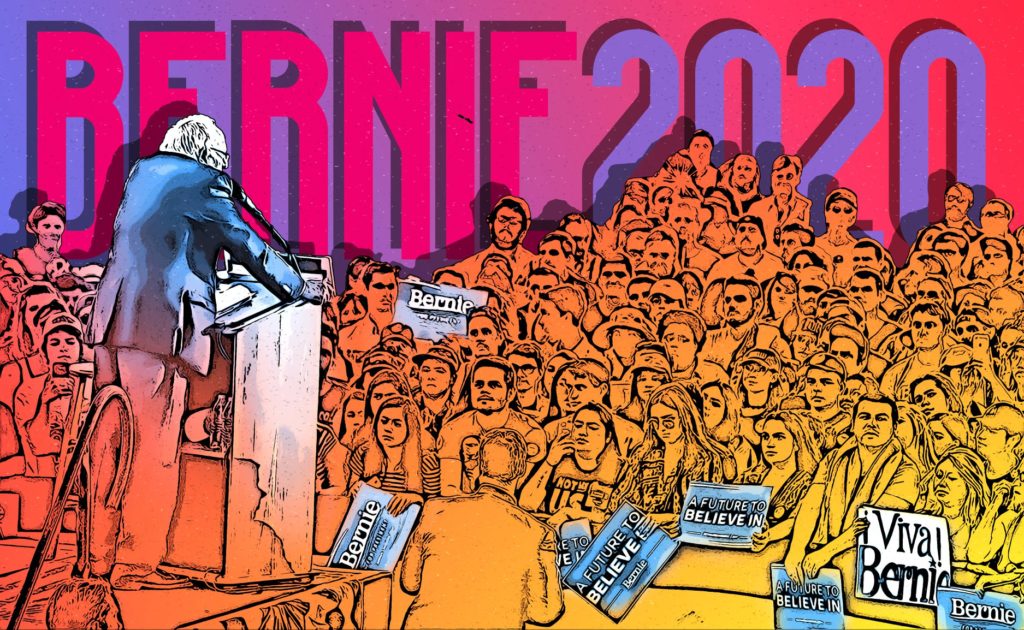

Behind these stunning growth numbers is a real opportunity for the “inside / outside” Bernie Sanders campaign. The fastest-growing group of voters in California isn’t happy with the political parties and needs a new message. And with California’s semi-open primary, these NPP independent voters - many of whom are registered for mail ballots in California’s increasingly postal voting-centric system - will simply have to return a postcard requesting a partisan primary ballot. The California Democratic Party has traditionally supported this practice, and even with establishment animosity towards Sanders in place, a huge influx of Berners in recent party elections bodes well for the mixed primary and enlarging the pool of Democratic Party voters, regardless of whether they’ve registered with the party.

I’ve been surprised, however, that Sanders supporters are missing the opportunity to educate and organize these party-free voters, who historically have turned out at much lower numbers than Republican voters. Instead of an education campaign, daily I see Berners on social media urging independent voters to re-register. This strategy simple does not reflect what is happening in our state. Motor voter is bringing new voters in, and if they can’t be convinced to support Sanders and request a crossover ballot, what evidence is there that they can be convinced to re-register to support Sanders?

As I look at 2020 and California’s early primary, this education and follow-up campaign is one of the top opportunities for Sanders’ movement candidacy. Others include using Facebook engagement advertising to activate younger and infrequent voters, and, using consumer data appends to identify likely unregistered, eligible voters and then organizing registration drives.

Aside from the issue of surging NPP registration, there remains the problem of California voters registering as American Independents in confusion. This right-wing party won’t have Democratic crossover ability and groups that want to reach these voters should consider engaging, educational ads targeted at voter file- and append-based custom audiences. We must also support AB 681, a bill by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego), which will increase the number of notices to voters about their registration and how to request a crossover ballot.

“We just want to make sure people understand that they have to make an affirmative step in order to vote in a presidential primary if they’re not registered as a partisan voter,” Gonzalez told the Los Angeles Times. “The different forms of communication can help if a voter misses one of them.”